Please see below for Brewin Dolphin’s latest ‘Markets in a Minute’ article, received by us yesterday evening 03/08/2021:

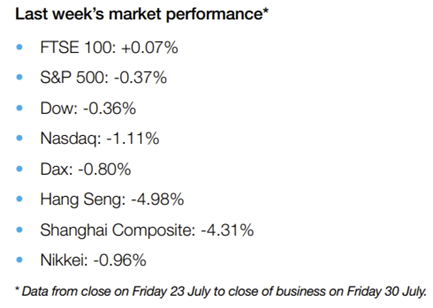

Global equities were mixed last week as weaker-thanexpected US economic data offset strong corporate earnings reports.

In the US, the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq slipped 0.4% and 1.1%, respectively, after gross domestic product (GDP) growth and durable goods orders missed expectations. Amazon’s warning of slower growth in the months ahead weighed on the consumer discretionary sector, whereas utilities and real estate stocks outperformed.

The pan-European STOXX 600 ended the week flat amid ongoing concerns about the spread of Covid-19. The UK’s FTSE 100 was also little changed after a spike in the number of people told to self-isolate continued to disrupt production.

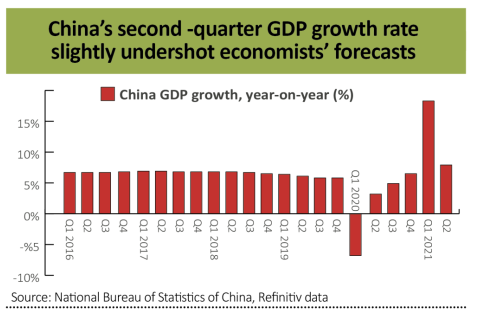

Over in Asia, Japan’s Nikkei 225 lost 1.0% as new Covid-19 cases reached record levels, resulting in Tokyo’s state of emergency being extended until the end of August. China’s Shanghai Composite slumped 4.3% following the country’s regulatory crackdown on the technology and education industries.

Delta woes weigh on markets

US stocks closed slightly lower on Monday as concerns about the Delta variant were compounded by softer-than expected manufacturing growth. The Institute for Supply Management’s index of national factory activity fell from 60.6 in June to 59.5 in July, the lowest reading since January and the second consecutive month of slowing growth.

Asian markets followed Wall Street lower on Tuesday, with the Nikkei 225 and Hang Seng tumbling 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively, as fears about the spread of coronavirus overshadowed strong US corporate earnings.

In contrast, the FTSE 100 and the STOXX 600 added 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively, on Monday, following news that British engineering firm Meggitt has agreed a £6.3bn takeover by US company Parker-Hannifin. Shares in Meggitt surged 56.7% from Friday’s close.

Market gains continued into Tuesday, with the FTSE 100 and the STOXX 600 up 0.4% and 0.3%, respectively, at the start of trading.

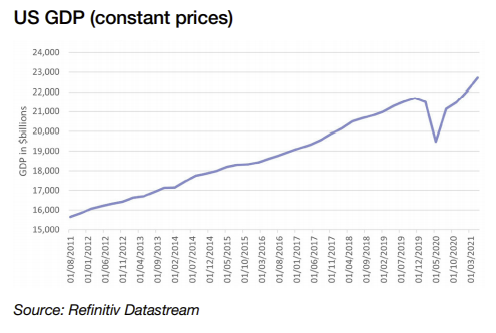

US economic data misses estimates

Last week’s headlines were dominated by the latest GDP figures from the US. According to preliminary data from the Commerce Department, the US economy expanded by an annualised rate of 6.5% in the second quarter. This was better than the 6.3% increase seen in the first quarter but was significantly below forecasts of 8.5% growth.

Personal consumption was the biggest driver of growth, as the stimulus cheques issued between mid-March and April fuelled an 11.8% year-on-year increase in household spending. This was partially offset by lagging property investments and inventory drawdowns.

Separate data from the US Census Bureau showed orders for cars, appliances and other durable goods in June were also weaker than expected. Orders rose by 0.8% from the previous month versus estimates of 2.2% growth, although May’s reading was revised up to 3.2% from 2.3%. It came amid continued shortages of parts and labour as well as higher material costs.

Meanwhile, the Labor Department reported that 400,000 people filed initial claims for unemployment benefits for the week ending 24 July, above the Dow Jones estimate of 380,000 and nearly double the pre-pandemic norm.

More positively, US consumer confidence was little changed in July, hovering at a 17-month high of 129.1. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast a decline to 123.9.

Inflation picks up in Europe

Over in the eurozone, inflation accelerated to 2.2% in July from 1.9% in June, according to figures from Eurostat. This was the highest rate since October 2018 and above the 2.0% reading forecast by economists. Higher inflation came amid faster-than-expected monthly GDP growth of 2.0% in the April to June period. Compared with the same period a year ago, GDP surged by 13.7%. The eurozone economy is still around 3% smaller than at the end of 2019, but the expansion marked a strong rebound from the 0.3% contraction seen in the first quarter of 2021.

Germany missed expectations with a quarterly expansion of 1.5%, as supply constraints left manufacturers short of materials such as semiconductors.

Half a million come off furlough

Here in the UK, more than half a million people came off furlough in June. The gradual reopening of the hospitality sector drove more than half the total fall in jobs supported by wage subsidies, according to data from HM Revenue & Customs.

Shortages of labour and materials and problems recruiting staff meant manufacturing output and order book growth slowed to its weakest level in four months in July. The manufacturing PMI stood at 60.4, down from 63.9 in June. IHS Markit said July’s performance was still among the best on record but would have been even better had it not been for supply constraints.

Nevertheless, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) upgraded its 2021 growth forecast for the UK to 7%, meaning that together with the US it would have the joint fastest growth of the G7 countries this year. In 2020, the UK’s economic contraction was the deepest in the group.

Please continue to utilise these blogs and expert insights to keep your own holistic view of the market up to date.

Keep safe and well

Paul Green DipFA

04/08/2021