Please see below for AJ Bell’s latest Investment Insight article, received by us yesterday 14/03/2021:

In some ways, markets had little to digest in the immediate wake of the Budget, as so much of the chancellor of the exchequer’s speech had made its way into the newspapers the previous weekend.

Rishi Sunak did come up with a couple of surprises all the same, in the form of the superdeduction for capital investment and his plan for eight freeports, designed to boost the UK’s trade flows in a post-Brexit world. The key issues raised by the Budget, at least from an investment perspective, passed unasked:

- Why should anyone lend the UK money (and therefore buy its government bonds, or gilts) when it does not have the means to pay them back?

- Why should anyone lend money to someone who cannot pay them back in return for a yield of just 0.77% a year for the next ten years (assuming they buy the benchmark 10-year gilt)?

- Why would anyone buy a 10-year gilt with a yield of 0.77% when inflation is already 0.7%, according to the consumer price index, and potentially heading higher, especially if oil prices stay firm, money supply growth remains rampant and the global economy finally begins to recover as and when the pandemic is finally beaten off?

Anyone who buys a bond with a yield of 0.77% is locking in a guaranteed real-term loss if inflation goes above that mark and stays there for the next decade.

In sum, do UK government bonds represent return-free risk? And if so, what are the implications for asset allocation strategies and investors’ portfolios?

GILT YIELDS ON THE CHARGE

The benchmark 10-year gilt yield in the UK has surged of late. It is not easy to divine whether this is due to the fixed-income market worrying about inflation or a gathering acknowledgement that the UK’s aggregate £2 trillion debt is only going one way – up. But the effect on gilt prices is clear, since bond prices go down as yields go up (as is also the case with equities).

This is inevitably filtering through to exchange-traded funds (ETFs) dedicated to the UK fixed income market. The price of two benchmark-tracking ETFs has fallen, albeit to varying degrees. The instrument which follows shorter-dated (zero-to-five year) gilts has fallen just 2% since the August low in yields.

Meanwhile, the ETF which tracks and delivers the performance of a wider basket of UK gilts (once its running costs are taken into account) has fallen 8% since yields bottomed last summer.

That 8% capital loss is at least a paper-only one, unless an investor chooses to sell now, but the yield on offer does not come even close to compensating the holder for that paper loss, which supports the view that bonds now represent return-free risk.

SAVING GRACES

However, the higher bond yields go, the greater the return they offer and that means at some point investors may decide that the rewards are sufficient compensation for the risks, especially as three arguments could still support exposure to UK gilts.

- The market’s fears of inflation could be misplaced. Bears of bonds have been growling about record-low interest rates and record doses of quantitative easing would lead to inflation for over a decade – and it has not happened yet.

If the West does turn Japanese and tip into deflation, even bonds with small nominal yields would look good in real terms and possibly better than equities, which would do poorly into a deflationary environment, at least if the Japanese experience from 1990 until very recently is a reliable guide.

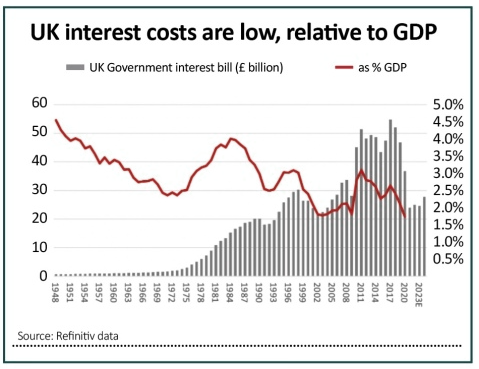

- The UK’s financial situation may not be quite as bad as it seems. Yes, the national debt is growing but the Bank of England’s monetary policy is keeping the interest bill to manageable levels.

The Government’s interest bill as a percentage of GDP has hardly ever been lower. That buys everyone time and is also why Sunak is tinkering with taxes, to convince bond vigilantes and lenders alike that the UK can and will repay its debts, as

it has every year since 1672 under King Charles II. A big leap in bond yields (borrowing costs) would be expensive.

- The Bank of England could move to calm bond markets with more active policy. Whether that calms inflation fears is open to question but financial repression (see a recent edition of this column) could yet come into play, supporting bond prices and reducing yields.

In sum, no-one has a crystal ball. Therefore, bonds could yet have a role to play in a well-balanced portfolio over time, but it is inflation, rather than risk of default, that looks likely to be the greatest threat to any holder of gilts.

Please continue to utilise these blogs and expert insights to keep your own holistic view of the market up to date.

Keep safe and well

Paul Green DipFA

15/03/2021