Please see the below article from JP Morgan received this morning:

China’s ESG reporting is on an improving trend, but investors still need to do their own work and fill in the gaps left by third-party providers to get the full picture.

Data is critical in any investment decision process. For sustainable investing, the requirement goes beyond financial statements – we need specific and comparable ESG data. However, the availability and quality of such data is a major challenge for investors, particularly those investing in emerging markets, including China.

Third-party ESG data providers tend to take a broad-brush approach in emerging markets, and don’t always apply local nuance. In particular, they can lack local language skills and focus on data and information published in English, often leading to significant information gaps. Even more than in developed markets, it is necessary for investors to lead with their own analysis rather than with third-party ESG research. Standards are often better than many foreign investors suspect – but it’s necessary to do the fundamental work and to be selective.

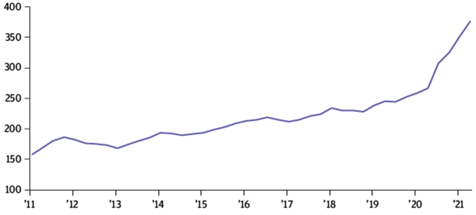

Chinese companies do report information related to ESG, and the trend of ESG reporting is positive. In 2020, 1,021 A-share companies issued ESG reports, representing 27% of all. This number is much higher for bigger companies, with 86% of CSI 300 constituents producing ESG reports in 2020, up from 49% in 2010.1 However, the content of ESG reports in China is highly qualitative. Quantifiable metrics, which are vital for investment analysis, are limited. The transparency of the methodology and the consistency of disclosure are additional concerns for investors. As with third-party providers, overseas investors without local language resources may sometimes struggle to get the full picture as companies listed only on the onshore market tend to report only in Chinese.

Looking at E, S and G data separately, the quality and availability of governance data stands out in relation to the other two, as in other parts of the world. This makes sense as governance has been subject to investor scrutiny for much longer. Measurable and comparable environmental data is also increasingly available, helped by the strengthening of regulatory requirements and commitments made by the authorities. In 2020, China made a surprise pledge prior to COP 26 to reach carbon neutrality before 2060, which should further drive the introduction of policies supporting the transition to a low carbon economy. Social data is more limited, but here too we expect regulation to help.

Exchanges and regulators are major stakeholders that the investment community is looking to for help in uplifting ESG reporting. Hong Kong Exchange is among the exchanges in Asia actively promoting ESG reporting and has introduced mandatory disclosure requirements. In the domestic markets, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) also plans to introduce new rules that could require more compulsory reporting of ESG data.

Environmental

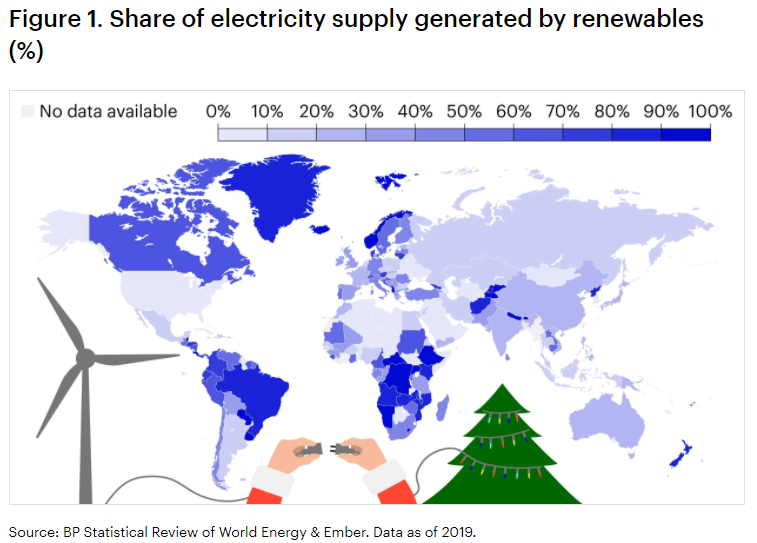

Rapid development since China opened up and reformed its economy in 1978 has resulted in economic prosperity but also the environmental challenges we are seeing today. The authorities recognise the need to control pollution and to preserve the environment for a more sustainable economy. This has been underpinned by proactive measures on environmental protection over the past five to six years. The refinement of the Environmental Protection Law stated the responsibilities of companies and their reporting requirements related to matters such as emissions and discharge of certain pollutants. These mandatory reporting regulations help not only the China government but also investors to assess the environmental protection efforts of local companies. While the amount of mandatory environmental disclosure is relatively limited in terms of both breadth and depth, the content is comparable with global standards.

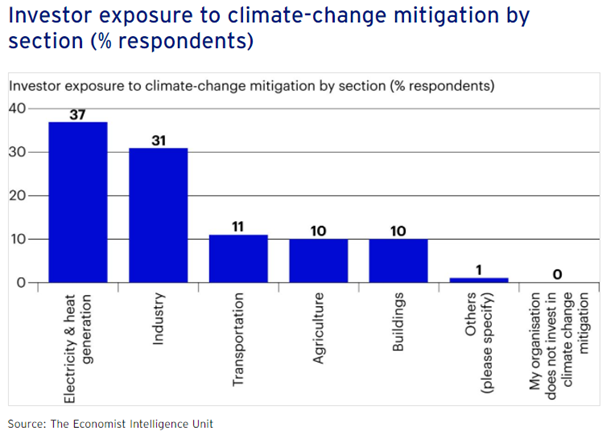

Following the carbon commitments made by China last year, investors are clearly expecting follow-through actions by the central government. Among the expectations for public companies is an uplift in the disclosure requirements of regulators and stock exchanges. Currently, the Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges do not make environmental disclosure mandatory for all companies. With the global demand for higher standards of climate reporting, which is at the front and centre of environmental reporting, we see a trend towards more exchanges and regulators making certain climate data disclosures compulsory. While not every piece of data is material and relevant to all companies, investors are looking for some critical data points, including Scope 1 and 2 emissions, which are comparable and necessary for measuring the environmental performance achieved by companies. More importantly, China needs greenhouse gas emission data from all companies to track the national roadmap to peak carbon by 2030 and carbon neutral by 2060. On the back of the water crisis that China and many other countries are facing, investors are also looking for greater transparency in water data.

We want accurate static data about environmental footprint, but what we need even more is forward-looking commitments and action plans. We believe that the risks and opportunities related to climate change can have a financially material impact. Today, disclosure on strategies, risks and targets for climate management are uncommon in China. When we engage with companies, we encourage them to align their reporting to an internationally recognised framework, such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). We are looking for expansive adoption of the framework in China.

Social

The Chinese authorities increasingly recognise that robust ESG disclosures and practices are necessary. As a result, they are increasingly implementing regulation, not only on environmental issues, but also related to areas such as labour rights, product safety and diversity – although enforcement still varies by sector and by region.

One element of the motivation for this increased focus is to attract overseas investors to the market. As China’s markets continue to open up, these overseas investors are demanding increasing levels of transparency and positive engagement: a virtuous circle. A major internet company came under scrutiny in January this year following the deaths of two employees – one sudden cardiac death and one suicide. The company is a classic tech stock with a highly driven work culture and long working hours – 9am-9pm, six days a week, is the standard in the sector in China. The company issued its first ESG report in November 2020, which was welcome progress. However, as a result of the increased investor engagement, it has now committed to further improvements in its disclosures, as well as to an action plan on working conditions, including health checks and the establishment of a transparent communication channel for employees to register problems.

Disclosure standards on social issues for some Chinese companies may also be driven to a significant extent by the companies they supply. In sectors including tech and retail, large western companies are closely scrutinised for labour practices in their supply chains, and have therefore pushed for increased transparency on these issues in China. Simply being aware that a local manufacturer forms part of the supply chain for a western organisation with rigorous practices is not a replacement for detailed analysis by investors; however, such an awareness can contribute both reassurance and another potential source of information.

Among domestic investors, too, there is a rising awareness of ESG issues, and although such issues are generally not currently driving investment decisions, we expect them to play more of a role in the future.

Governance

For investors, governance is a foundational precept that underpins public markets. China presents investors with a large economy, in which the state is an active actor. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) offer investors a wide range of options, but are commonly subject to different governance norms and priorities versus privately owned enterprises. This dissonance requires a nuanced approach to mitigate potential risks. In some cases, privately owned onshore enterprises lag their state-owned counterparts around disclosure standards, especially around related party transactions. However SOEs are also not free of potential governance concerns: senior management positions are largely appointed by the Chinese government, with crossover between government officials and SOE boards implicitly raising risk of conflict with investor and creditor interest. The Chinese government has begun to make progress around SOE reform, introducing more professional management, but the scale of the challenge makes progress appear small, albeit determined. We note an increasing number of independent board directors, especially in listed SOEs, where awareness of external rating assessments are more pronounced.

In the private sector, Chinese regulators have been investigating accounting issues and forcing enhanced disclosure, with more public sanctions following evidence of wrongdoing. As a result, the depth of financial disclosure has improved. In response to the negative cost of capital impacts that follow scandal, Chinese family businesses are also showing improvement, through the hiring of professional management or other steps to reduce key employee risk.

We would still like to see increased transparency from both state and privately owned enterprises, including greater clarity around segregation of duties and evidence of awareness of ESG issues. We welcome companies and issuers making greater efforts around investor education, particularly those that make senior executive time available to investors. Overall, we note an improving governance framework evolving in China, with increased investor interaction an area of improvement. The overall standard remains lower than US companies, though improvements on the China side are narrowing the gap.

Conclusion

Overall, we consider ESG data disclosed by Chinese companies still to be insufficient. But this should not rule out sustainable investing in Chinese companies. With the help of on-the-ground fundamental analysis and alternative data, and through active corporate engagement, investment managers can still integrate ESG factors into investment research and create value for their investors.

With a stronger push from regulators, exchanges and investors, we expect Chinese companies to disclose more, better ESG data over time. Higher transparency through the ESG lens would allow investors to better understand the risks and opportunities of companies they invest in. This is critical in driving sustainable investing to the mainstream in China.

1 An Evolving Process: Analysis of China A-share ESG Ratings 2020 by SynTao Green Finance

Our Comment

The above article is interesting as accurate data is one of the key components for our ESG due diligence process.

The article highlights issues with China’s ESG data, but looking at the bigger picture, the rest of the world also has a way to go when it comes to data.

We have to watch out for ‘greenwashing’ which we have written about before, and make sure that the investment providers are doing what they say.

One of the key ways we avoid these data issues is by using multi asset or discretionary fund managers for our ESG offerings.

This makes sure that the investments we recommend are actively managed and that the investments have a strong ESG process built in, which is done by specific and experienced teams of fund managers.

This also helps us to reduce any concentration risk in one market sector and diversify an overall portfolio.

We have an ongoing dialogue with these fund managers and our due diligence is a constant ongoing process which helps us to ensure that the investments we recommend are managed exactly as the fund managers say they are.

As ESG stays under the spotlight and becomes an integral part of investing, the more accurate and reliable data reporting will become. ESG data reporting is in its infancy.

Keep an eye out for more ESG related content from us.

Andrew Lloyd DipPFS

16/08/2021