Please see the below article from JP Morgan received this morning:

‘Emerging markets pose particular ESG challenges. But factoring ESG considerations into decision making can benefit performance, and demand for more sustainable investments is helping to drive change.’ – Tilmann Galler

In our 2021 Investment Outlook, we outlined that one of the key imperatives for investors in 2021 was to understand how the global policy and regulatory initiatives behind environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors are likely to increasingly affect the macro landscape and financial sustainability of companies.

In this context, should investors shy away from investing in emerging markets given lower standards? In this piece we consider the diverse array of ESG challenges that exist in emerging markets and argue that selecting companies that are rising to the challenges and navigating a changing ESG landscape can lead to significant return opportunities, as we have already seen in recent years (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: ESG leaders outperformed in emerging markets

Index level in USD, rebased to 100 at December 2010

Environment (E):

Preserving the environment and fighting climate change are becoming increasingly pressing global policy priorities. With President Biden now in the White House, the Paris Climate Agreement has been invigorated, and the discussion is likely to intensify ahead of the important regroup at the COP26 meeting in November.

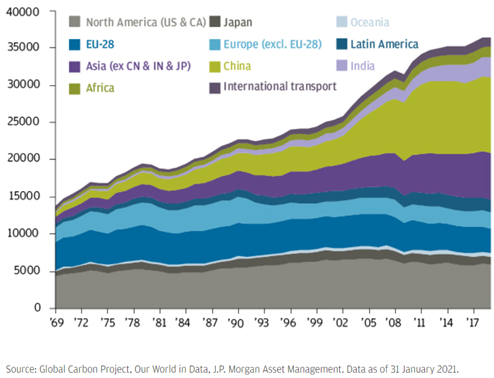

Reducing carbon emissions and aiming for carbon neutrality have been identified as important milestones. Fifty years ago, today’s developed countries contributed two thirds of global carbon emissions and emerging markets only one third. Today, total CO2 emissions have tripled, but the ratio has reversed and emerging markets contribute almost 70% (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Emerging markets are the biggest contributor to CO2 emissions

Annual total CO2 emissions by region from fossil fuels and cement production only; million tonnes

Europe and the US have committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, while China has given itself an additional 10 years. Reaching these goals will require a significant alteration to the business fundamentals of corporations in carbon- intensive sectors such as energy, materials and utilities, but also for fossil fuel-dependent economies such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa. Business and economic models that fail to adjust will likely face increasing sanctions from investors and climate-committed governments.

A prominent example is the carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is currently being discussed in Europe and the US with the aim of avoiding regulatory arbitrage.

The adjustment would take into account the carbon intensity of goods sold. Countries that did not set a sufficient carbon price would be perceived to be gaining a competitive advantage and so would face tariffs at the border. But implementation is complex. Any carbon border adjustment has to be embedded into existing obligations under the World Trade Organisation and should also relate to local emissions trading schemes. There is also a risk that such a mechanism could fuel further trade conflicts and in the end evolve as a new frontier in the US-China trade war.

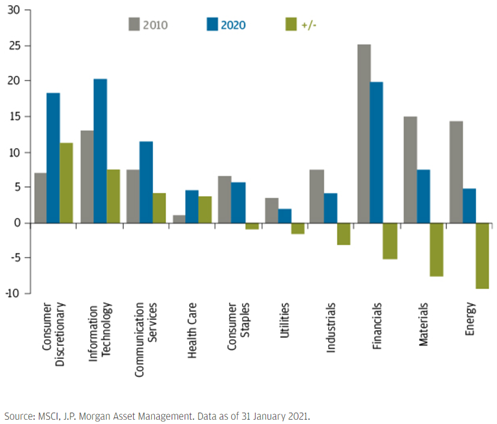

As emerging economies mature and services become a larger part of their economies, their CO2 footprints will naturally improve. We have already seen a significant decline in the market cap weighting of carbon intensive sectors in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (Exhibit 3). Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly in manufacturing, food processing standards, and water and waste management. Governments may be resistant to change if it is perceived to be an impediment to GDP and income growth. But emerging market companies that are part of an international supply chain will have to improve their standards, because large multinational companies are beginning to optimise their value chains for ESG criteria. Failing to adapt will be a significant disadvantage in the global competitive landscape. We therefore expect that transition will, in many cases, be faster on a corporate level than in government policy.

Exhibit 3: MSCI Emerging markets sector weights

Social (S):

Human rights, labour and health conditions, and diversity are social criteria on which businesses operating in emerging markets are facing increased scrutiny. Growing awareness from consumers and investors worldwide is putting governments and corporates under pressure to improve – with social media bringing increased visibility of the issues. The Foxconn labour abuse controversy is a good example. Reports of poor working conditions in the company’s Chinese factories, where it manufactures products for Apple, created a very negative global feedback loop. Companies exploiting employees and the communities they operate in are risking significant reputational damage on a global basis.

Governance (G):

While environmental and social factors are gaining prominence, governance issues such as regulation, corruption, transparency and share-/bondholder rights have long been important considerations for investors in emerging markets. World Bank Indicators provide a useful top-level indication of the countries that require particular investor vigilance and those that already have higher standards in place (Exhibit 4). However, it’s important to keep in mind that these indicators provide just a snapshot of the current status and that the dynamics in corruption and regulation are quite different across the regions. In the past 10 years, Asian countries, on average, have showed significantly more improvement than Latin American, where the situation has deteriorated. Even if countries are engaging in more sustainable policy and introducing stewardship codes, like Korea,Taiwan, and Brazil in 2016, results can differ widely. The investment world will watch China’s next five-year plan closely to see whether financial sector reform and stricter environmental regulation will also improve government stewardship.

Exhibit 4: Corruption control and regulatory quality per country

Percentile rank indicates the country’s rank among all countries covered by the aggregate indicator, with 0 corresponding to lowest rank, and 100 to highest rank.

A key issue in emerging markets on a corporate level is ownership. The free float of the MSCI Emerging Markets is only 50%, compared to nearly 90% for developed markets. Investing in emerging markets generally means that you are in a minority position, because the entity is controlled by either the state, individuals or families. The risk for investors is that the company management is not only pursuing economic goals. Close relationships to government officials are also detrimental to efforts to fight anticompetitive practices, corruption and bribery and protect shareholder rights. Engagement is crucial to get a clearer picture of the management’s commitment to improving governance. Compared with developed markets, the power to induce change through voting in shareholders’ meetings is more limited.

However, policymakers in emerging markets are reacting to the increased demands for better governance. For instance, the introduction of corporate governance codes in Taiwan (2010), Brazil (2016), and Russia (2014) improved the representation of independent directors on boards. In emerging markets overall, such representation has increased by 10 percentage points to 51% in the past four years. Governance standards in South Africa are already close to those in developed markets.

Exhibit 5: Governance is improving in emerging markets

Average % of independent directors in selected emerging markets

Conclusion

Emerging markets and ESG represent the place where two investment mega-trends come together. The dynamic growth of emerging markets will lead to a significantly higher representation in portfolios in the next 10 years. At the same time, due to investor preferences and developed world capital regulation, we are seeing a growing preference for investments that meet ESG criteria.

Emerging markets are not homogenous on a country nor a corporate level. But growth and sustainability can be reconciled through careful company research and engagement. Companies that are the beneficiaries of fast growth in their local markets, but which at the same time demonstrate an awareness and desire to meet global ESG standards, have sustainable business models. Indeed, ESG characteristics often serves as a proxy for quality, since companies that screen well are often managed with a long-term view, with higher levels of broad R&D and innovation.

In summary, we do not see that investing in emerging markets sits in opposition to the world’s broader ESG ambitions – the opposite might be the case. By demanding higher ESG standards, investors are helping to accelerate the pace of change. The scope for improvement in sustainable outcomes is significant and the consideration of ESG factors in this asset class provides ample return opportunities for long-term investors.

Please continue to check back for more ESG related insights along with our usual market updates and commentary.

Andrew Lloyd

08/03/2021