Please see the below article received by AJ Bell late yesterday:

A report from BP suggests demand for crude has already peaked.

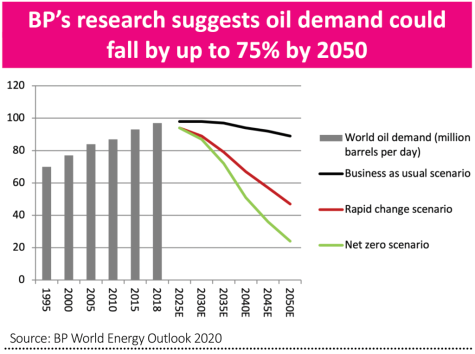

Oil major BP’s (BP.) latest annual World Energy Outlook, released in conjunction with a three-day presentation from chief executive Bernard Looney and team outlining the oil major’s new strategy, offers three scenarios for demand for crude oil in 2050.

They range from 89 million barrels a day, barely 10% below 2019’s peak of 98 million as nothing much changes politically or socially, all the way down to 24 million, as the world goes carbon neutral.

The possibility that oil demand could go down by three-quarters between now and 2050 means Looney’s desire to prepare BP for a zero-carbon world is perfectly understandable.

It also leaves investors with a decision to make. Those willing to select individual securities on their own must now decide whether to place their faith in Looney and the company’s ability to reinvent itself. Its plan is made all the more complicated by weak oil prices depriving BP of vital cash flow, just when it needs to invest heavily in both its new strategy and the maximisation of value from hydrocarbon assets where there are already considerable sunk costs.

Those who wish to avoid the rough and tumble of stock-specific risk and prefer to use active or passive funds must still assess their potential for exposure to BP and other oil stocks.

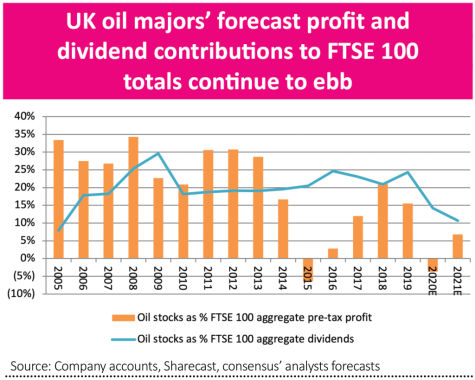

This is particularly the case in the UK, where analysts’ consensus forecasts for 2021 assume that BP and Royal Dutch Shell (RDSB) will generate between them 7% of total FTSE 100 profits and 11% of the headline index’s total dividend pay-out.

WANING WEIGHTING

Whether such forecasts are reliable, too optimistic or too conservative will be especially important for investors in FTSE 100 tracker funds, as they indirectly own BP and Shell whether they like it or not.

For those investors who do not wish to embrace oil stocks, for financial or philosophical reasons (or both), it is worth considering the following:

- From a dividend perspective, the oil majors’ combined forecast pay-out represents its lowest portion of the FTSE 100 total since 2005;

- From an earnings perspective, BP and Shell’s contribution is way lower than it was in 2005, when they generated one-third of FTSE 100 profits between them.

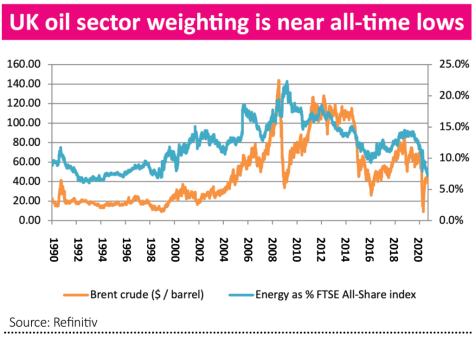

These numbers at least explain why oil shares are doing so badly. The FTSE All-Share Oil & Gas Producers sector is now worth just 7.1% of the FTSE All-Share itself, a fraction above 1992’s modern-day low of 6.3% and almost identical to 1998’s cyclical trough of 7.0%.

Those dates are interesting because BP cut its dividend in 1992 (just as it has done this year), while crude oil prices dipped briefly below $10 a barrel in late 1998, just as they did this spring.

On a global basis, oil shares’ weighting in the S&P Global 1200 index and America’s S&P 500 benchmark stands at record lows of 2.9% and 2.2% respectively. The S&P 1200 Energy index’s valuation of $1.3 trillion means the industry currently carries a lower price tag than Microsoft and is worth barely four times more than Tesla, whose current car volume sales are tiny, at least for now, at around 100,000 units per quarter.

Investors with exposure to individual oil firms, specialist energy funds (be they active or passive) or geographic stock indices with a hefty exposure to oil companies (which would include the FTSE 100) must now decide if this marked bout of oil stock underperformance is merely cyclical or the result of something more structural.

If BP’s zero-carbon scenario holds true, even the most wilfully contrarian investor may struggle to make a case for exposure to oil stocks, at least until the earnings mix begins to truly slant away from hydrocarbons, as it is hard to divine what could be a catalyst for higher oil prices and thus higher earnings.

Yet if the ‘no change’ case pans out, owing to political or social inertia, the picture could be very different. Demand could recover in a post-pandemic world and do so just as oil majors cut investment, US shale output falls and global oil rig activity is down more than 50% year-on-year.

That could make for a surprise cyclical comeback from an industry that financial markets seem to be writing off – the FTSE All-Share Oil & Gas Producers index rose 50% in 2016, the year after BP and Shell last made a combined loss, just as they are forecast to do in 2020.

Whilst hard to predict, as you can see from the above article, the suggestion is that oil demand could go down by three-quarters between now and 2050 as the world strives to be ‘zero-carbon’. The lockdowns imposed by governments due to the pandemic have shifted peoples focus more than ever to a ‘green’ ‘zero-carbon’ world.

Please continue to look out for our regular blog posts.

Andrew Lloyd

21/09/2020