Please see the below article from AJ Bell published earlier this week and received yesterday:

The past 12 months have been a bit of a mixed bag from a portfolio point of view.

Yes, the US equity market stands at a record high, and Germany and India reached new peaks in the autumn, while the FTSE 100 has, as of the time of writing, chalked up a solid, double-digit percentage capital gain, with dividends on top. Oil surprised with a near-40% gain.

But Brazil and China are down for the year, gold has done nothing and some of the air has started to leak out of some of the more speculative areas of the market: Bitcoin has shed a quarter of its value, Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovations ETF has collapsed, and the record of new market floats is looking patchy both in the UK and globally. The US markets regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), is even talking about tightening up the rules on Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) just as its British equivalent, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), bizarrely loosens them.

“The US equity market stands at a record high, and Germany and India reached new peaks in the autumn, but Brazil and China are down for the year, gold has done nothing and some of the air has started to leak out of some of the more speculative areas of the market.”

As a history graduate, this column is a great believer that you need to understand the past before you can take a view on the future. These five trends from 2021 could yet make their presence felt in 2022, so they are worthy of further study, especially if advisers and clients are preparing to do a New-Year review of their strategic asset allocation plans for portfolios.

1. UK money flows

The average capital gain from an Initial Public Offering (IPO) on the London Stock Exchange is some 20% at the time of writing, which looks perfectly healthy, especially for a sample of almost 100 deals. However, the range of returns is wide, from a trebling to a drop of 77% and only half generated a positive return: for every success like Oxford Nanopore there has been a flop like Deliveroo and even Darktrace has shed a lot of its early gains.

Such stock-specifics will be of little interest to time-pressed advisers and clients. They pay fund managers to sort the wheat from the chaff. But IPOs are important because a real boom in new offerings is often the sign of a market top – that certainly proved to be the case in the UK in 1999-2000 and 2006-07. It often works out that way because the quality of deals goes down as stock indices – and risk appetite – go up and misallocation of capital and subsequent losses bring down the curtain. As the old saying goes, “bull markets ends when the money runs out.”

IPOs are important because a real boom in new offerings is often the sign of a market top because the quality of deals goes down as stock indices – and risk appetite – go up and misallocation of capital and subsequent losses bring down the curtain. As the old saying goes, “bull markets ends when the money runs out.”

The good news at least is that the flow of IPOs (and for that matter secondary capital raisings by firms that are already listed) is nowhere near the levels seen near past peaks in the FTSE 100.

According to the London Stock Exchange website, primary listings have totalled £14.7 billion and secondary offerings have soaked up a further £24.7 billion of portfolios’ cash.

But ordinary dividends from the FTSE 100 alone will exceed £80 billion according to analysts’ estimates in 2021. Moreover, members of the UK’s leading index have already declared £5 billion in special dividends and nearly £19 billion of cash returns in the form of share buybacks. That lot comes to over £100 billion, and then come the proceeds from the 70-odd bids for UK-listed firms of all shapes and sizes.

The good news at least for advisers and clients with exposure to the UK equity market is that the money is not running out, to suggest the UK market has upside potential in 2022, providing the new offering pipeline is kept to sensible levels.

2. Oil

Oil’s near-40% gain to date in 2021 will have surprised many an adviser and client, but uranium and even coal were strong markets too, despite the tide of public and political opinion, which has swung even further toward alternative and renewable sources of energy, especially after the COP26 summit.

Yet demand for energy continues to grow and renewables are not yet producing sufficient capacity to take the baseload strain. That means hydrocarbons are still important, whether we like it or not, but supply is being constrained, partly by the machinations of OPEC and its allies, partly by geopolitics (and sanctions against Iran and Venezuela) and partly by oil firms themselves. Fund managers are pressuring them to invest in renewables or simply disinvesting, Governments are refusing to sanction fresh exploration and insurers are declining to insure new projects.

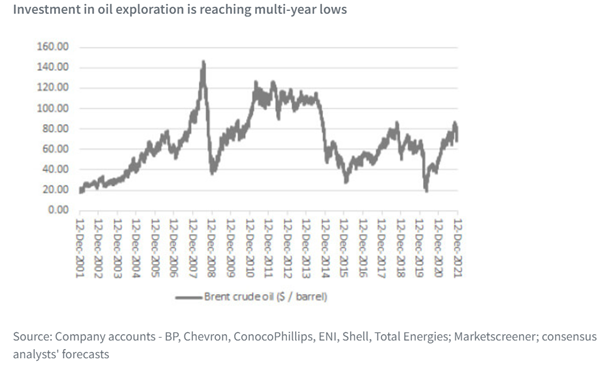

“The aggregate capex-to-sales ratio of the seven oil majors is heading toward multi-year lows. This could create a supply-demand squeeze if the economy shakes off the latest strain of COVID-19 and keeps growing. And higher oil prices, if that’s what we get, could play a major role in shaping inflation.”

Not surprisingly spend on drilling is under pressure: the aggregate capex-to-sales ratio of the seven oil majors – BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, ENI, Shell and Total Energies – is heading toward multi-year lows. This could create a supply-demand squeeze if the economy shakes off the latest strain of COVID-19 and keeps growing. And higher oil prices, if that’s what we get, could play a major role in shaping inflation, so watch this space in 2022.

3. The Misery Index

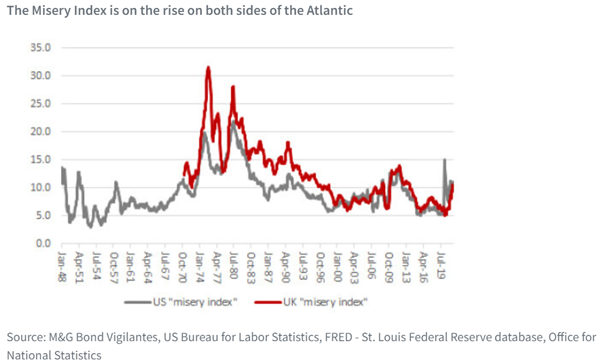

This column is indebted to a conference hosted by M&G’s Bond Vigilantes team for reminding it of the importance of the Misery Index.

Developed by economist Arthur Okun in the 1960s, this indicator simply adds together the prevailing rate of unemployment and the prevailing rate of inflation. As such, it defines the balancing act which central banks face when they set policy. For the past few years – and certainly since the pandemic – unemployment has been central banks’ number one preoccupation and they have run ultra-loose monetary policy as a result. But galloping inflation means the misery index is going higher, even if unemployment is coming down, and policymakers must now decide whether to start tapering Quantitative Easing and raising interest rates as a result.

The Omicron variant complicates calculations, but the Misery Index would suggest that action may be required (especially if oil prices catch light again).

4. Bonds

There will be no spoilers here, just in case any adviser or client has yet to get round to seeing the latest 007 film, No Time To Die. But 2021 was no fun for anyone who had a large allocation to Government bonds in the view that disinflation or even deflation would be the defining macroeconomic theme of the year (in a continuation of the trend of the prior decade).

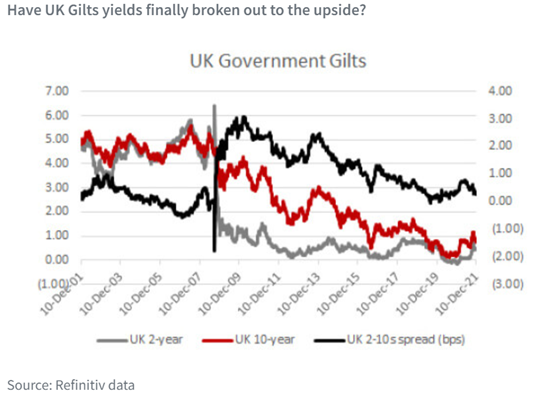

“The question now is whether a trend toward lower Government bond yields and higher prices, that dates back to the early 1980s and Volcker-led Federal Reserve in America and the Thatcher-Lawson axis in Government in the UK, is decisively broken or not.”

Using the UK as a benchmark, Gilt yields rose and prices fell, as inflation picked up pace and the Bank of England had to confront the prospect of whether to start tightening monetary policy. The question now is whether a trend toward lower yields and higher prices, that dates back to the early 1980s and Volcker-led Federal Reserve in America and the Thatcher-Lawson axis in Government in the UK, is decisively broken or not. The chart does suggest a break-out but we have seen many false signals such as that in the last four decades.

5. Central banks

Unfortunately, no discussion of financial markets can be complete without an assessment of central bank policy, as the above commentary makes only too clear. The monetary authorities have their fingers in more pies than Mr. Kipling: interest rates have been kept at historic lows since spring 2020 and Quantitative Easing, asset-buying programmes designed to suppress interest rates, force cash into financial markets and create a so-called wealth effect mean that balance sheets have ballooned. In aggregate, the balance sheet of the Bank of England, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Swiss National Bank and US Federal Reserve has grown by:

- $9.5 trillion since the start of 2020 – that is 67%

- $13.0 trillion over five years – that is 99%

- $ 17.4 trillion over 10 years – that is 199%

“Do a 0.1% base rate and £895 billion of Quantitative Easing in the UK seem appropriate when the Office for Budget Responsibility is forecasting 6% GDP growth, 4% inflation and just 4.8% unemployment for 2022, at a time when house prices are rising at their fastest rate for 15 years, asset prices more widely are elevated, and parts of the financial markets are feeling positively bubbly?”

On the face of it, tighter policy makes sense. After all, do a 0.1% base rate and £895 billion of Quantitative Easing in the UK seem appropriate when the Office for Budget Responsibility is forecasting 6% GDP growth, 4% inflation and just 4.8% unemployment for 2022, at a time when house prices are rising at their fastest rate for 15 years, asset prices more widely are elevated, and parts of the financial markets are feeling positively bubbly?

The Omicron variant of COVID-19 complicates decision-making and central banks are clearly weighing the danger of inflation on one side against the threats posed by unemployment, higher interest costs in a massively indebted-world and sagging asset prices (and perhaps thus consumer confidence) on the other. It is a difficult balancing act and one that will have huge implications for advisers’ and clients’ portfolios in 2022 and beyond.

Some central banks are already acting. The Bank of Canada has stopped adding to QE, the Reserve Bank of Australia and US Federal Reserve are tapering their bond-buying programmes, while there have been 94 interest rate increases from central banks around the world this year, against just 11 cuts. However, none of those 94 have come from the big five in the UK, EU, Japan, Switzerland and US and they will have to prove in 2022 that they are ahead of the curve and not behind it, if markets are to keep the faith in policies which have done so much to stoke risk appetite in equity markets and suppress bond yields in fixed-income ones for more than a decade.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term.

Please continue to check back for our latest blog posts and updates.

Andrew Lloyd DipPFS

23/12/2021